Crunch, Crash and Burn: The Darker Side of the Games Industry

- Caitlin Jordan

- Feb 4, 2019

- 6 min read

▲ People playing computer games at Gamescom 2019 in Cologne, Germany. Photograph: Magnus, Unsplash

The games industry generated £2.87bn for the UK economy in 2016, and the British Film Institute who published the report found that the industry made up 47,620 jobs. With growing accessibility to games and yearly blockbuster releases, the video game sector is thriving, but at what cost?

The video game sector is regarded as a “hobby” industry. The prevailing messaging is that one should consider themselves “lucky” to be doing a job that they “love”. It is a highly competitive labour market as people are willing to do whatever they can to get ahead in the sector. Companies benefit from this as workers sell their craft for the lowest price, just so they can be in an industry they love.

The beginning of 2018 saw the launch of Game Workers Unite (GWU), an international grassroots organisation dedicated to advocating for workers' rights in the games industry. GWU UK, a branch of the organisation is the very first union for video game workers in the country. The union hopes to tackle issues such as excessive overtime, sexism and the lack of diversity within the workforce.

Overworking in the industry is a widespread problem. According to the International Games Developers' Association’s (IGDA) 2017 survey, 51 per cent of game developers said that their job involved “crunch time”. The term “crunch” refers to workers putting in long hours of unpaid overtime, often in the run-up to anticipated releases. They trade in their time, relationships and health in order to meet the tight deadlines.

Declan Peach, founder and vice-chairman of GWU UK, says that “crunch culture” comes from the vicious cycle of publishers trying to release games under progressively tighter schedules.

A game that would feasibly take a year and a half to make, would be given only a year. The studios given these deadlines then enforce a culture that encourages more overtime: “People often feel bad leaving at the right time because they would be the first one doing it. That’s the problem with crunch culture, everybody wants to work as much as they possibly can because they want to do well in this industry.”

Peach adds that there is an issue of diversity, not just in the games sector, but in the tech industry in general. ‘GamerGate’ was a social media harassment campaign in 2014, which targeted several women in the video games industry. Targeted harassment, rape and death threats highlights how hostile the environment can be for women and minority groups.

The 2015 Gender Balance Workforce Survey found that 45 per cent of women felt that they had encountered obstacles to their career progression due to their gender. 45 per cent also experienced forms of bullying or harassment whilst in the industry. According to a GamesIndustry.biz survey, two-thirds of game companies worldwide do not have appropriate mechanisms in place to deal with harassment or abusive behaviour.

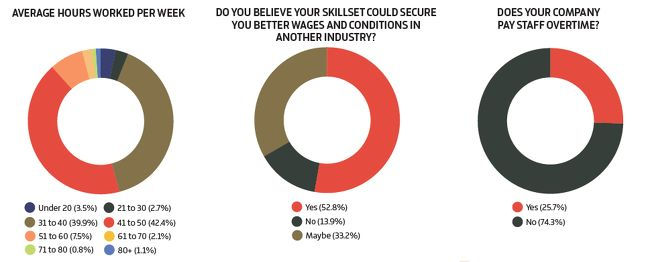

▲ Survey results looking at the working conditions in game companies. Source: GamesIndustry.biz

I reached out to the Equality and Human Rights Commission about whether or not video games companies had safeguards in place to prevent harassment and discrimination, but received no response.

Game designer Hannah Nicklin has been subjected to micro-aggressions and sexism: “Sexism in the games industry is exacerbated by the technical mind-set and customer base and audience that may see the industry as a place not for women and marginalised people.”

Nicklin says that she wants to see women’s work and activism being showcased. “Very often women, people of colour and marginalised groups are asked to provide their suffering as a means of learning. I would much rather men share experiences of when they made women uncomfortable due to mistakes they’ve made,” she says.

While issues of diversity and inclusivity are common, the game industry’s biggest mishap still remains to be crunch culture. Liam Welton is a game developer who has worked for numerous indie studios. While working on a project, he and many of his colleagues were working past their contracted hours. “This is something unfortunately true with a lot of smaller independent developers, just slipping into overtime without really realising it. But where do you draw the line on how voluntary it is? If everyone is doing it, there’s an amount of pressure for you to do it as well,” he says.

Narrative and game designer, Ross Kennedy, worked on a project with a nine-month deadline. The project was backed by a big publisher, with a release date that coincided with a multimedia release, so no changes could be made to the schedule. During this period, Kennedy recalls colleagues working constantly, skipping lunch hours and staying as late as nine o’clock. On one occasion, the team stayed in the office until 1am.

Kennedy did not receive pay for his overtime and says that his contracted hours did not feel enforced. “A lot of contracts are left open-ended enough and are basically written to say, ‘You will work on this project, but also where else is needed’. Bear in mind, this was at a company that did not support crunch. The fact that it’s a place where crunch still happened so harshly and so frequently for that project, I can’t imagine what it’s like working for a bigger place that can enforce crunch year-long,” he says.

An article in New York Magazine last October sparked controversy after Dan Houser, vice president of Rockstar Games, described employees working “100-hour weeks” in the run-up to Red Dead Redemption 2’s release.

Dan and Sam Houser, the company co-founders and creative leads on the game, would frequently change and discard large portions of the games. Throughout the eight years of development, major changes were made to the story, presentation and gameplay mechanics. It is a common practice for games of this nature, but this led to excessive overtime.

▲ Red Dead Redemption 2 (2018). It was marketed as a video game that pushed the limits of game innovation, but the company gained criticism for the treatment of employees. Photograph: Rockstar Games

Kennedy says: “Red Dead Redemption 2 was marketed as an integrated world, with an (in-game) economy, dynamic animal behaviour and weather. Because of such a grand vision of what the game was supposed to be, the work was supposed to reflect that. A lot of studios want to push towards a game of that level and the only way is through putting in all the time and resources possible.”

He adds that game developers are under pressure from both the company and its fans: “If there are any glitches in a game because of rushed production, the general feedback is ‘your game’s not good enough, make it better.’”

Remarkably, Red Dead Redemption 2’s controversy was met with fans in support of game developers having better hours and pay. “The reaction is different to what I usually see regarding crunch and game developers. There’s an argument about whether or not people should be aware of the conditions when purchasing a game. But you could also say, should people be aware of purchasing an iPhone if it’s made by exploited workers around the world?” Kennedy says.

I ran a survey that asked, “Would you continue to purchase products from a company that mistreats its workers?” Out of the 50 respondents, 54 per cent said “yes”. Although all voters agreed that the companies should reimburse their workers, 32 per cent believed that the employees were responsible for their own situation. For instance, one of the respondents said, “It was their choice to work in an industry known for overworking its staff.”

There is an assumption that game developers are lucky and should be incredibly grateful for the opportunity to make games as a living, despite the poor pay and hours. “The truth about the games industry is that it’s hit-driven and you don’t particularly have a secure job. But you still need to have incredible technical skills, that are highly transferrable. I’ve gotten really close to burnout myself and it’s widely known that the average length of time people spend in the industry is five years,” says Welton.

The GamesIndustry.biz survey saw that 53 per cent of game developers believe that their skillset could secure better wages and conditions in another industry.

Despite the horror stories and negative reputation the industry holds, new graduates remain starry-eyed and driven by dreams of success when applying to companies.

Aside from developing games, Nicklin has also been a guest lecturer for multiple universities. In her experience, students go into game development due to its “golden ticket” narrative. “Everyone else doesn’t matter and it’s the idea that you will be the one who succeeds. Although there are stories of crunch, the idea is that ‘you are talented, you are special, and you are the one who will succeed and make millions’. This is what instils self-crunch and self-exploitative behaviour,” she says.

Nicklin says it is vital to acknowledge what GWU can do. People can hold on to their golden ticket, but it’s much more likely that they reach burnout before they achieve anything substantial.

GWU is opening up conversations about solidarity and communication, and Nicklin believes it is a step in the right direction: “In uniting with other people, that collective bargaining power will improve conditions for everyone. It may not be the golden ticket, but it’s a silver ticket where everyone, including yourself, will be better off.”

Comments